Baby it’s getting hot in here. Irritated and covered in sweat, yet again my two year old daughter is struggling to sleep in her cot. I’ve now lost count of the number of nights that the baby thermometer has scowled at me for putting her to bed in officially dangerous temperatures.

The ongoing heatwave is the main topic of everyday conversation these days, with record-breaking temperatures and wildfires covering newspapers’ front pages and the NHS issuing health warnings for vulnerable groups.

Yet there has been a deafening silence about the likely key driver – climate change.

I am staggered at how difficult it is for us as a society to talk about the links between climate change and extreme weather events like heatwaves. Most people have no problem talking about the links between lung cancer and smoking, even if they aren’t lung cancer specialists. But whenever I’ve brought up the subject of climate change in conversations about the heatwave with people around me, they’ve quickly changed the subject.

It simply will not be possible to achieve broad and sustained bottom-up demands for action on climate change without taking every possible opportunity to help people connect the dots. Only when people understand the risks posed can they be expected to respond and be part of the changes needed to limit those risks.

Guardian columnist Zoe Williams recently wrote about the heatwave this indicative comment: “Some build-up of brain bacteria over time compels you to mention climate change whenever there is any weather anywhere, but you remember from the 90s that everybody hates that person, so it’s better to just head off weather chat mildly, absentmindedly – ‘hot? I suppose it is’”.

A quick analysis of search term trends in the UK over the past few weeks demonstrates that while there is a significant spike in searches for ‘heatwaves,’ there has been no accompanying increase in searches for ‘climate change’.

Even among those in the climate change movement, there is a reluctance to raise the issue. When I spoke to a senior climate change communicator the other day, he said: “I think people are feeling jaded about this.”

So whilst the vast majority of people in the UK and around the world understand and acknowledge the scientific facts behind climate change, there is far less acknowledgement in everyday reality.

This climate silence worries me deeply. How can we adapt our homes to deal with increasing extreme weather events, protect those most vulnerable in our communities, or act on the causes of climate change if – even when we are experiencing the reality of scientific predictions – we don’t even dare mention it?

Climate change is difficult to talk about for many reasons, but I am convinced that unless we manage to turn climate change from a scientific to a social reality, we will never be able to tackle it.

As my colleague George Marshall wrote, ‘our brains are wired to ignore climate change’. The last twenty years of traditional environmental campaigning have largely added to this psychological disconnect. Grasping this reality is empowering. We increasingly understand the best ways for ‘talking climate‘ and being able to do so effectively around droughts, floods and other extreme weather events is a vital part of connecting wider society with climate change.

Though weather isn’t climate, it is through the weather that we encounter the climate. Whereas climate change is psychologically distant for most people in both space and time, extreme weather events can provide a clear personal connection with the issue.

There is evidence that warm weather can drive belief in climate change. One study of 89 countries found that when temperatures rise above the seasonal average, so does belief in climate change. It also found that in the US, for every degree rise in temperature above the preceding 12 month average, there is a 7% increase in belief in climate change.

Another study of donation behavior to environmental groups showed people were more likely to make donations when outdoor temperatures at the time the study was conducted were perceived to be warmer, relative to cooler, than usual.

So people’s direct experience (as opposed to messages about global averages) is an important factor.

But there are other issues to consider. For example, talking about – or visualising the impacts of – climate change on a local area can make people feel overwhelmed or emotionally numbed. Localising climate change can run the risk of triggering defense mechanisms such as denial.

For that reason it is important to connect messages about impacts with narratives that offer solutions and actions people can take in response to these risks.

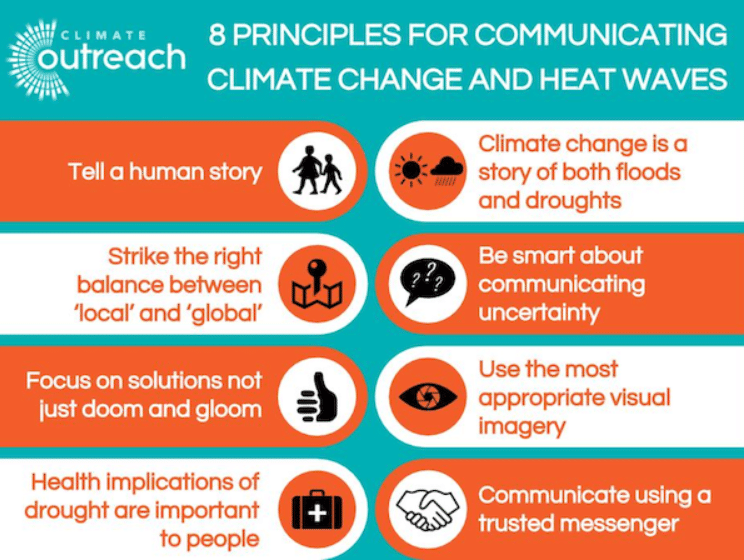

In working to support people and organisations to more effectively communicate around droughts and heatwaves, our research has lead to the development of a set of principles – see below – to help anyone wishing to have these conversations.

Whilst it isn’t easy to do, we are increasingly understanding the best ways to allow people to see themselves in the climate change story, whether they are care home managers worried about their elderly residents, Mancunians watching their hillsides burn, or parents struggling to get their kids to sleep.

Previously published on Climate Home

One response to My baby can’t sleep from the heat, why aren’t we talking about climate change?

Sign up to our newsletter

Thank you for signing up to our newsletter

You should receive a welcome email shortly.

If you do not receive it, please check your spam folder, and mark as 'Not Spam' so our future newsletters go straight to your inbox.

“they’ve quickly changed the subject.”

I had a chilling moment reading an excellent book on the experience of ordinary Germans during WWII when I identified the same phenomena was observed if you tried to mention the murder of the Jews in polite company. And yet there must have been thousands of Germans who felt like we do about climate change. What was lacking in that case was a coordinated response to the crisis with the support of some of the leadership groups that enjoyed a degree of immunity from the worst persecutions of the Nazis (namely the church). Fortunately we don’t risk brutal reprisals in western countries at least but the same need is there to deal firstly with the resistance to engagement manifested by the bystander effect – the way each individual says to themselves: “It can’t be up to me”.