This think piece was written by our researcher Dr Susie Wang, with the help of our former Director of Programmes and Research – and now Associate – Dr Adam Corner, and our Executive Director Jamie Clarke.

Over the last two decades, certain debates and disagreements have defined the discourse to campaign and engage the public on climate change.

Hope vs. fear!

Debunking deniers vs. engaging the sceptics!

And perhaps more than any other…

Individual lifestyle change vs. system change!

Often formulated as dichotomies instead of fluid spectrums, these disputes can feel esoteric, or even self-indulgent to those outside of the climate space. But they are more than quaint communications quibbles – they have driven the assumptions and theories of change that have in many ways defined the climate movement.

Where you stand on these issues has often dictated the kinds of activities and goals that you think constitute effective activism. And the question of whether ‘lifestyle changes’ are a positive and necessary part of curbing climate emissions, or a distraction from the serious business of systemic change, has rumbled on and on.

Prominent polemicists and influential scientists have frequently waded in, often taking an unnecessarily one-sided perspective – although perhaps the most prominent climate voice of the current generation, Greta Thunberg, takes the view that the actions of individuals (especially high-profile and norm-setting campaigners) can’t be easily untangled from the systemic change they advocate for.

From false dichotomies to a deeper understanding of lifestyle change

At Climate Outreach, the question of how to better communicate (and ‘mainstream’) low carbon lifestyles, has become an increasingly important focus of our work. This has evolved over the past decades, fostered by texts such as George Marshall’s Carbon Detox, Tom Crompton’s path-breaking work linking altruistic values, low carbon lifestyles, and systematic change for WWF, and the work of environmental psychologists like Linda Steg, Lorraine Whitmarsh and Ezra Markowitz.

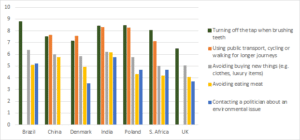

Figure 1: Responses across seven countries to the question: “To what extent do you feel that the following actions have an impact in terms of protecting the environment?”. Around 1,000 participants in each country indicated their answers for five different behaviours (e.g. avoiding eating meat) using a score of ‘0’ for ‘no impact at all’ (makes no difference taking this action) to ’10’ for ‘very large impact’ (makes a very great difference). The chart’s Y-axis relates to this scoring system. Please note: The question about ‘contacting a politician’ was not asked in China. Source: Mainstreaming Low Carbon Lifestyles report (p27)

As the evidence base has developed, so has Climate Outreach’s perspective. The sector has largely moved away from the pursuit of individualised, ‘simple and painless’ private-sphere behaviour change, and towards a recognition of engaging people on the ‘behaviours that matter’ by engaging values, motivations, and worldviews.

Some theoretically promising concepts – such as behavioural ‘spillover’ where one action (such as recycling) leads to another (reducing air travel) – have been hard to realise in practice. Many older climate campaigns equating significant action on climate change (‘Save the Planet!) with minor changes (‘By re-using your coffee cup!’) have been rightly ridiculed, and although the tide is surely turning on them, they persist even today in the parts of the campaign world that have not yet received the climate-emergency memo.

And some ideas that have gained significant traction – the so-called ‘nudge’ approach and the now very-broadly-defined ‘Behavioural Insights’ field – have a role to play but could certainly use much more critical scrutiny. As the ‘Talking Climate: From Research to Practice in Public Engagement’ book argued, it is necessary to shift from ‘nudge’ to ‘think’ if the magnitude of the climate challenge (and what’s required from ordinary citizens) is to be effectively represented. The risk of compartmentalising individual behaviours is that nowhere is the ‘big picture’ of the climate crisis present in the public mind.

And it is this ‘big picture’ that has shaped Climate Outreach’s work on lifestyle change in recent years.

Climate Outreach is proud to be one of the founding partners of the Centre for Climate Change & Social Transformations (CAST). The centre is focused on the novel and rich concept of people as agents of change who can think, act and engage in very different ways (and at different scales) on climate change. As the figure below illustrates, changes in ‘lifestyles’ could be private-sphere tweaks to energy habits, or they could be decisions made in a professional context as employees, they could be a commitment to lobby an MP or support a campaign – people and their agency to create change, not simply wait passively for ‘system change’ to arrive from above, are the key to unlocking faster progress on climate change.

Figure 2. People as agents of change. Source: Adapted from CAST

A new agenda for lifestyle change

The work Climate Outreach has started with CAST has coincided with what feels like a definitive change in the discourse. The idea that behaviours and lifestyle change matter is no longer a contentious one, and the idea of public engagement no longer needs to be reduced to minor adjustments in relatively inconsequential energy or travel decisions.

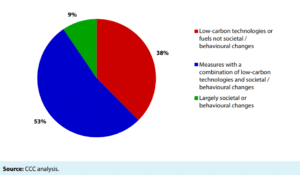

Through initiatives such as CAST, the 1.5 Degrees Lifestyles project led by Lewis Akenji, scholarship from researchers like Diana Ivanova, Ilona Otto, and Stuart Capstick, advocacy through meticulous research on wealth and carbon inequality by organisations like Oxfam, shifts in the perspectives of philanthropic funders such as the KR Foundation, and (belatedly) a recognition in some policy circles that people’s attitudes, behaviours and active consent are crucial to the transformations ahead (Figure 3), the discourse on low-carbon lifestyles is beginning to shift. This is bolstered by in-depth synthesis work, such as the recent Cambridge Sustainability Commission report outlining key levers and intervention points for deep and rapid change.

Figure 3. The role of technological and societal and behavioural change in driving low carbon transitions. Source: The UK Climate Change Committee

For Climate Outreach, perhaps the clearest sign of the shift is the agenda-setting United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Emissions Gap report which contained – for the first time – a chapter on The role of equitable low-carbon lifestyles in closing the emissions gap.

A collaboration between Climate Outreach, CAST, Oxford University, and a list of expert co-authors, the chapter positioned lifestyle change and system change as two sides of the same coin. The chapter put forth that lifestyle change is interrelated with system change, and both are necessary to reduce global emissions to meet global targets. This is important particularly for those in the global richest 1% and 10%, who emit far more than their fair share. There is a need to focus on key sectors and meaningful lifestyle changes that are likely to create the largest reductions in emissions, and there are various ways to facilitate such changes, through mechanisms at the individual, social, and system levels.

These key messages were not ‘invented’ for the UNEP chapter, but their synthesis represents the clearest yet indication of how the discourse on lifestyle change vs. system change has shifted. However, there’s a lot more work to do.

How can we talk about lifestyle change?

Lifestyle changes have been seen as controversial topics for public engagement, but the more nuanced approach towards lifestyle change as a product of interrelated processes at the individual, social, community, and system level opens up opportunities for more effective communication.

In some ways, the lessons we know from general public engagement also apply; that when engaging with an audience, it is important to understand their context, and focus on the values, cultures, and norms that underpin certain aspects of lifestyles, whether it’s the way people live, what they eat, or how they travel. These are essential in understanding intervention points to create an effective lifestyle change, as well as to ensure that proposed lifestyle changes make sense to, and resonate with the public.

Similarly, we can utilise the power of stories to translate complex topics or help showcase sustainable ways of living that are difficult to imagine. Anecdotal accounts from peers can also be powerful. Stories about how “people like me” are changing their ways of life convey a social norm that can lead to wider change, as well as building a sense of confidence and self-efficacy in being able to have an impact.

We can also build support for low-carbon lifestyles by communicating their multiple benefits, for instance, conveying that low-carbon dietary and transport choices are often also healthier, and low-carbon infrastructure and housing in terms of insulation and clean heating can result in a better quality of life. In developing and emerging economies, huge amounts of infrastructure decisions will be made in the next ten years, which will lock in lifestyle choices at a scale that will define whether climate targets can be met or are doomed to fail. Campaigns around the multiple benefits of low-carbon infrastructure and policies may help to increase public acceptance or pressure, and “lock-in” low-carbon options into the future. Here we see the relationship between systemic and individual change clearly signaled – but with the chance still to choose the sustainable path.

Next steps in bringing about rapid and equitable lifestyle change

However, there are still many questions moving forward. Through engagement activities around the release of the UNEP report, Climate Outreach has been listening to and strategising with stakeholders from around the world, drawing from across research, policy, advocacy, and strategic communications. Through three online discussion sessions, attended by leading thinkers and actors working on catalysing climate action (and the role of low carbon lifestyles within this), we have scanned the frontier of the low carbon lifestyles discourse to distil key issues for communicating and achieving low-carbon lifestyles.

Public engagement on lifestyle change needs to focus on the audiences and behaviours where intervention can make the most difference. One of the key messages from the UNEP chapter is around the stark carbon inequality between the global richest 1% or 10% and the poorest 50%, directly driven by wealth inequality. Here we see the old truism that climate change is fundamentally a question of justice through the precise quantification of emissions inequality at a global scale. The ‘lifestyles’ of the highest emitters must change if there is any chance whatsoever of achieving global climate goals. And key learning in discussing this imperative has been that persuading the people who comprise the 1% or 10% that they are in fact in this category is the first challenge. How can we convince the richest 1% or 10% that they must change their lifestyles rapidly and dramatically?

Put simply, the world of highly concerned but high-emitting Western professionals must now move from concern to action – and be supported to do so by rapid structural shifts that can facilitate a low-carbon lifestyle. As this (large but minority) group shifts, their cultural/soft power and social influence will provide a powerful message that wealthy people with agency and influence can ‘practice what they preach’. It will also enable those who are living low-emitting lifestyles, many of whom do not have access to adequate standards of living and wellbeing, to increase their quality of life.

A simultaneous goal for public engagement around low-carbon lifestyles is to begin a dialogue to reimagine “a good life”, one that is compatible with a low-carbon world. Given the relationship between income and overconsumption, how can we move beyond the idea that “well-being” and “progress” have to be tied to standard views of “affluence” and “growth”?

Perhaps more fundamentally, the language we use to communicate on lifestyle change (as a fundamental part of system change) needs to be developed to keep pace with the discourse. Even the two sides of the same coin framing arguably suffer from the same linguistic and conceptual constraints that have characterised previous ‘stand-offs’ between different camps on this issue. Even with an explicit recognition that changes in some behaviours by some people are a critical piece of the climate puzzle, the idiom doesn’t quite capture the fact that changes in the lives of people (‘lifestyle change’) are necessarily and unavoidably part of what “system change” is – and vice versa. There is a need to communicate the interconnectedness of systemic and individual change. Can we think about system change and lifestyle change as the hardware and the software, social practices and behaviours as the programmes that run on the ‘hardware’ of decisions made about transport infrastructure, agriculture, or commerce? We understand well enough that one is worthless without the other: is this a better analogy than ‘two sides of the same coin’?

Currently, there is very little peer-reviewed evidence for hard-hitting policies and their impact, meaning there’s a mismatch between our aims (1.5-degree lifestyles) and how we can get there. This means that for public engagement, there is a gap in communications, where we are not able to advocate solutions as strongly as we can our targets. In finding these solutions, we have a lot to learn from socially inclusive, rapid transitions in history, and from each other. A better understanding of the learning and lessons from energy or wider technological or socio-political changes in the past is an urgent requirement for catalysing transformations in the present day on climate change. Similarly, learning between nations is important: at a city level (e.g. C40) we see evidence of best practices being shared around climate policies, including how to structure policies that city residents will be more likely to engage with. But is this happening at the level of national governments? Learning between nation-states around prompting low-carbon lifestyles could help mainstream effective approaches where the social science/climate policy interface is operating well.

Beyond public engagement, there is a crucial challenge in the way that consumption emissions data is collected, synthesised, and shared: often it is delayed several years which means our knowledge of consumption emissions is consistently out of date or aggregated so much as to be almost useless for targeted policymaking. While it is possible to link consumption emissions to disposable income and track measures like GDP, linking consumption to variables like political orientation, class, or even basic demographics is harder. As a starting point emissions data need keeping ‘up to date’ on a quarterly basis in the same way that GDP is. And finding a way to move from the abstract aggregation of emissions ‘groups’ like the ‘1%’ and translating that into national and city-level targets for supporting certain individuals and communities to undergo rapid transitions based on an equitable distribution of responsibility, is where things need to be.

A need for a common compass

Moving forward, addressing these ongoing challenges, among others, will be crucial. While there is growing consensus that there is a need for equitable widespread lifestyle changes, there is simultaneously a need for opportunities and a knowledge and expertise network that allow us to work together to achieve this.

We have been working with our colleagues across many organisations (including the Hot or Cool Institute, One Earth, The Rapid Transition Alliance, Forum for the Future, and the Stanley Centre for Peace and Security) to develop a common “compass” to steer us towards sustainable lifestyles. Those working to achieve an equitable low-carbon world can align efforts in the most effective way by agreeing on a common end goal and principles, even as methods to achieve that goal may vary. With a compass to guide us, we can make sure we are working towards a common future, as well as identify strategic partnerships and working groups to align as a sector.

We are very grateful to all who contributed their time and thoughts to the stakeholder sessions: M. Graziano Ceddia, Joyashree Roy, Fletcher Harper, Molly Brown, Simon Maxwell, Kate Power, Tim Gore, Vanessa Timmer, Lewis Akenji, Lina Fedirko, Lorraine Whitmarsh, Diana Ivanova, Nikki Fitzgerald, David Hall, Jill Kubit, Stuart Capstick, Tom Athanasiou, Ilona Otto, Peter Newell, Christoph Gran, Lydia Korinek, Richard Dryburgh, and Andrew Simms.

2 responses to Low carbon lifestyles: what have we learned, and where do we go from here?

Sign up to our newsletter

Thank you for signing up to our newsletter

You should receive a welcome email shortly.

If you do not receive it, please check your spam folder, and mark as 'Not Spam' so our future newsletters go straight to your inbox.

such a great initiative i appreciate it and try to change my lifestyle also. best wishes to all your team, and the great cause you stand for.

In discussing the influence of ‘low carbon lifestyles’ the following web site might be of interest https://familyclimateemergency.net/

Given that everybody will have to adopt a low carbon lifestyle and zero carbon by 2040 (if not earlier) this changes involved should be seen as having some influence during the transition. I am not sure that the ‘think piece’ latched onto the power of money? Pension providers are well aware of the fragility of investments on fossil but can’t collapse these funds with their clients’ money invested. However, in short time the three As are more likely to save the planet than governments; Actuaries, Analysts and Algorithms?

The Uk government is beholden to the Climate Change Committee committed to “maintaining existing levels of comfort and standards of living”.