What’s really driving public beliefs about climate change?

In looking at how to close the psychological distance between the public and climate change the wider narrative, social norms and elite cues are crucial10.

Public attitudes to climate science are no longer seen as straightforwardly attributable to a lack of knowledge (the so-called ‘deficit model’ of science communication)11.

Values, along with worldviews and political ideology, are much more fundamental in shaping views about contentious issues in environmental science than people’s level of knowledge about a particular subject12.

Values are ‘guiding principles in the life of a person’, and are distinct from beliefs or attitudes, in that they are relatively stable and fixed13.

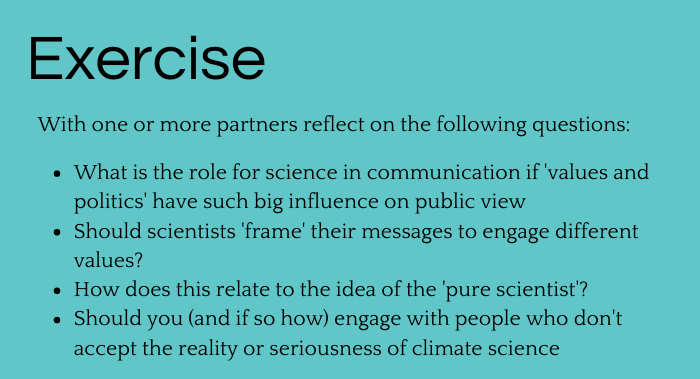

How can you start from the values the audience holds rather than the facts you want to get across?

People have a range of values, and may draw on different ones at different times, but certain types of values cluster together (while others conflict with each other).

In particular, ‘self-enhancing’ values like wealth, status and power (lower left quadrant of Image 1 below) conflict with ‘self-transcending’ values like altruism and concern for the welfare of others (top right quadrant of Image 1 below)14.

Promoting or ‘priming’ one type of value (e.g. by talking about the economic rationale for energy saving – a self-enhancing value) is likely to inhibit or weaken the prominence of competing values.

It is the self-transcending values which are most strongly correlated with concern about climate change, whilst endorsement of free-market economics and ‘self-enhancing’ values are associated with higher climate change scepticism.

The goal is to build a bridge between these types of values, to find messages which speak to both.

Recent research has shown that the desire to avoid wasting energy is a motivating message across the political spectrum15.

As you can see in Image 2 below, the idea of taking action to reduce energy waste, for example through poor insulation, is one that speaks to broad social norms (conformity), responsible behaviour and moderation – not being profligate with the use of energy.

This language associated with conservation acts as a bridge between self-enhancing and self-transcending values.

Reflect on the importance of values

The content of these webpages draws on a series of workshops created and developed by Climate Outreach and the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research as part of the Helix project.

10 Brulle, R.J., Carmichael, J. & Jenkins, J.C. (2012). Shifting public opinion on climate change: an empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the U.S., 2002–2010. Climatic Change, 114 (2), 169-188. doi:10.1007/s10584-012-0403-y

11 Sturgis, P. & Allum, N. (2004). Science in society: Re-evaluating the deficit model of public attitudes. Public Understanding of Science, 13, 55–74. doi:10.1177/0963662504042690

12 Corner, A. & Clarke, J. (2016). Talking climate: From research to practice in public engagement. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46744-3

13 Schwartz, S.H. (1992). Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. United Kingdom: Academic Press, Inc.

12 Schwartz, Shalom, Cieciuch, Jan., Vecchione, Michael et al. 2012. ‘Refining the Theory of Basic Individual Values.’Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 103, 663–688

14 Whitmarsh, L. & Corner, A. (2017). Tools for a new climate conversation: A mixed-methods study of language for public engagement across the political spectrum. Global Environmental Change, 42, pp. 122-135. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.12.008

Image credits:

Illustration by Barbara Govin created during the workshop held in Paris in September 2017

Images 1 & 2: Schwartz, S.H. (1992). Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. United Kingdom: Academic Press, Inc