As 2021 kicks off, Jamie Clarke reflects on his early days as Climate Outreach’s Executive Director eight years ago, when climate silence still needed to be broken. Since then we’ve reached the foothills of public engagement with climate change, but we can also see how steep the remaining challenge is, and what the priorities for overcoming barriers in 2021 need to be.

When I took the helm of Climate Outreach eight years ago I remember being both exhilarated and intimidated.

Exhilarated because I knew how vitally important building a social consensus on climate change was, and could see the key role the organisation had in achieving this. But intimidated by what seemed a gargantuan, almost impossible challenge: at the time, climate change was a phrase rarely uttered in conversations outside of the environmental bubble.

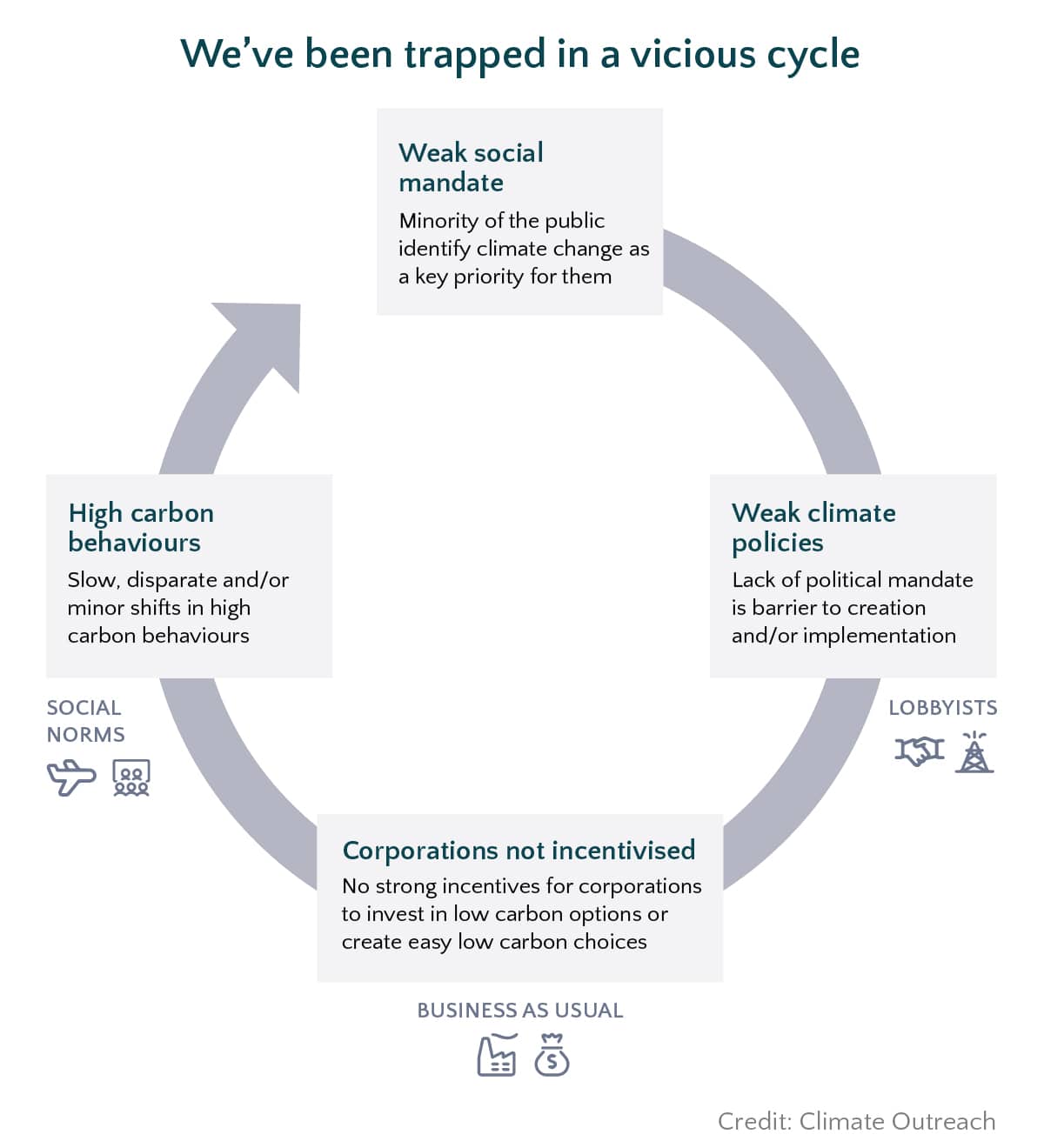

Imbued for many with the identity and views of a minority of environmentalists, or something for the world’s scientists and politicians to worry about down the line, even the term ‘climate change’ drove intense media debate about its validity, and polarised politics in many countries. A situation that was fueled by disinformation campaigns and vested interests created a vicious cycle and resulted in climate change being a very low concern for most people.

It was clear that a key reason the international community wasn’t getting to grips with the challenge of climate change was the lack of a strong social mandate. Climate advocates needed to focus not just on government policies, technology and financing, but also on breaking the climate silence, overcoming polarisation and enabling everyone to be part of the conversation of how to transform society.

Tellingly, I remember saying to one of my family members at the time that my new job was with an environmental charity, knowing full well that announcing I was heading up one of the few (at the time) dedicated climate change charities would trigger a very awkward moment.

Within this context, during one of my first internal strategic meetings at Climate Outreach, I said that we might consider ‘our job done’ once climate silence was broken, climate concern was consistently high amongst the public and the issue was no longer politically polarising.

Job done?

Fast forward to the start of 2021 and in many respects we’ve never had it so good in terms of public support for climate action.

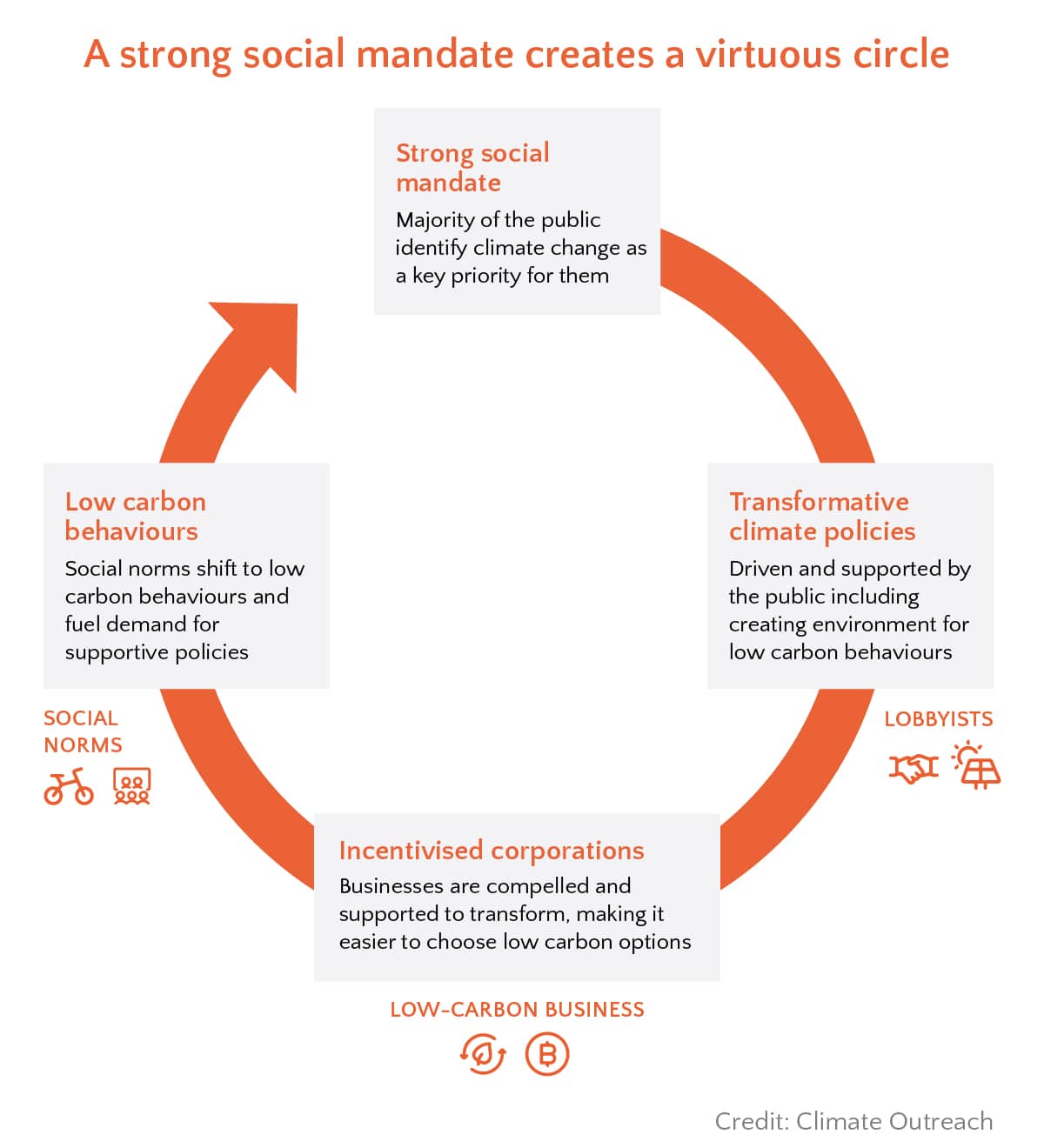

Climate silence has been shattered in many countries, with polls around the world showing sustained high levels of climate concern. In parallel (and not unrelated), there has been a shift in the mainstream media discourse, with the focus increasingly on reporting on climate impacts and the urgency of the climate crisis, rather than the scientific validity of climate change. Low carbon behaviours are no longer considered to be just the preserve of a minority; and politicians, including those on the centre-right, are signing up to (more) ambitious national climate targets. And all of this has persisted despite the seismic impact of Covid-19.

This puts the world in a much better position to make the right decisions in a year that will host the Glasgow UN climate conference, and as economies and societies rebuild in the context of the ongoing pandemic.

Polarisation and public engagement

Polarisation is still hampering action in many nations including the USA, Australia and Brazil. It’s vital that we build a cross-societal consensus on climate change – which is a long way off in fractured nations like the USA. Without this consensus, any administration’s positive climate policy legacy can be eroded by a future government.

In other countries, climate change still isn’t a high priority for the public. Often this is because there’s a lack of a national conversation, or at least one that resonates with the identities of wider communities. In countries such as the ones we’ve been working with in North Africa, communities may well be experiencing the negative impacts generated by climate change but aren’t necessarily connecting them with the wider causes and consequences of climate change.

We’ve seen in the past how people’s finite pool of worry has meant that climate has slipped down the priority list in the face of economic recessions. So far the Covid-19 crisis hasn’t triggered this; and indeed for many the pandemic has underlined the importance of addressing the climate emergency. In countries such as the UK it appears we have a solid foundation of climate concern.

A steep challenge ahead

What is more open to question is how the practical implications of the transformations required across society and everyday life will be accepted and embraced by citizens and politicians.

Transforming high carbon industries, shifting our workforces to low carbon jobs, reshaping how we heat our homes, how we travel and what we eat, are very tangible challenges which we’ve yet to negotiate. Similarly while we know that these are prudent investments, how they are paid for will inevitably come into sharper focus for the public. Working positively with those whose income, quality of life and identity feel under threat from net zero policies will require great care.

In many ways we’ve reached the foothills of public engagement with climate change; now we can see how steep the remaining challenge is for us to reach the top.

Priorities for building strong public engagement in 2021

2021 is going to be a key year for climate change policy but also for public opinion. Key to building on strong societal concern and and overcoming barriers will be:

-

- Ensuring the COP26 story is one that all communities in the UK can relate to and support, in a similar way to the 2012 London Olympics.

Stepping away from policyspeak and staged photo shoots of politicians and to an engaging narrative that speaks across communities via relatable and trusted messengers is going to be crucial. Our campaigns will need to speak across society and do so guided by the best research, such as Britain Talks Climate and wider public engagement understanding.

-

- Raising the voices, concerns and stories of individuals and communities who are not represented in the traditional climate change agenda.

We need to increase ownership of climate change action beyond the environmentally concerned and move to a situation where it is something that everyone feels they have a stake in.

When communities are being asked to make substantial shifts in long established work or behaviours, recognising that others like them are prepared to step up and shift social norms is crucial. Creating a just transition needs to be steeped in the concerns of those communities most implicated.

-

- Create the public engagement infrastructure necessary for long term transformation

Widespread social acceptance isn’t a function of one-off advertising campaigns or singular initiatives. It will require the same type of infrastructure as has been developed for other aspects of climate action.

Governments need to deliver on commitments to effectively engage their citizens through education and public awareness campaigns, but also around specific policy initiatives.

At Climate Outreach we are about to launch an international initiative to do exactly this, holding governments accountable to the commitments they have made in climate change agreements but on which there has been very little action so far.

Future family conversations?

I no longer have to feel sheepish around the family dinner table/zoom call when it comes to my work on climate change, but what will I be saying in another 8 years time?

Will I, whilst tucking into my plant-based meal, feel awkward discussing the rise of low carbon industries and the decline of fossil fuel companies with my sister, who currently works for a large oil and gas company?

Will it be an easy conversation to talk about providing financial support to those around the world forced to migrate because of climate impacts?

And will the conversation flow when talking with my Irish cousins who are of farming stock

about my local council rewilding agricultural fields around Oxford to reduce the risk of flooding?

I hope so but I certainly know that the work to ensure this happens starts now.

This blogpost is kindly supported by the KR Foundation

Sign up to our newsletter

Thank you for signing up to our newsletter

You should receive a welcome email shortly.

If you do not receive it, please check your spam folder, and mark as 'Not Spam' so our future newsletters go straight to your inbox.